Diffing Images and Using Columnar LSB to Retrieve a Message

Categories: forensics

2021-08-08

by skat

This writeup is also readable on my GitHub repository and personal website.

This is a writeup for another “forensics” challenge that I completed at UIUCTF 2021 where I took a rather unconventional and possibly even unintended approach to the challenge in order to arrive at a solution. I put “forensics” in quotes because I personally don’t really believe steganography to fall under the category of digital forensics, albeit I understand why others may make that association. This challenge involves performing columnar LSB steganography on an image, and I took the additional step of comparing it with a variant image in order to more precisely find a starting point.

forensics/capture the :flag:

Challenge written by spamakin.

It’s always in the place you least expect [sic]

Right off the bat, I’m suspecting that this is some kind of LSB steganography challenge; the description references the place we would “least” expect. There’re no given files, but the title of the challenge suggests that any relevant files may be found on Discord since :name: is the syntax for an emoji on Discord. There’s a flag emoji on the UIUCTF 2021 server:

Sure enough, downloading the image from Discord gives us a PNG to work with:

Checksum (SHA-1):

d565835e0b40a93e2c6330c028b7e153f7d00a6c flag.png

If we look at the image’s included metadata using a tool like exiftool, then we can see a hint in the description:

ExifTool Version Number : 12.26

File Name : flag.png

Directory : .

File Size : 2.4 KiB

File Modification Date/Time : 2021:08:03 23:50:33-07:00

File Access Date/Time : 2021:08:03 23:52:48-07:00

File Inode Change Date/Time : 2021:08:03 23:52:48-07:00

File Permissions : -rw-r--r--

File Type : PNG

File Type Extension : png

MIME Type : image/png

Image Width : 120

Image Height : 120

Bit Depth : 8

Color Type : RGB with Alpha

Compression : Deflate/Inflate

Filter : Adaptive

Interlace : Noninterlaced

Description : Pixels[1337]

Image Size : 120x120

Megapixels : 0.014

Interesting. “Pixels[1337]” implies that there’s something going on with the 1337th pixel in the image. Let’s load it up in Python and have a look. I don’t have high hopes since a single pixel in an RGBA image would only be able to communicate 32 bits of information, but let’s entertain the hint anyways. Here’s some Python code and its output:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from PIL import Image

def main():

img = Image.open("./flag.png")

pix = list(img.getdata())

print(pix[1337])

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

(136, 153, 166, 255)

Alright, well that didn’t tell us much. Let’s try changing them to hexadecimal to see if there’s some 8-character message with only 0-F digits. Again, I don’t have high hopes, but I’d rather entertain the thought and then strike it out than never try and never know:

88 99 A6 FF

That… that doesn’t tell us anything useful. Let’s go back to my initial hunch that this is an LSB steganography challenge and assume that “Pixels[1337]” was actually meant to be “Pixels[1337:],” in Python slice notation implying that all pixels from the 1337th index and onwards contain relevant data as opposed to singularly just the 1337th pixel. If an entire flag were to be encoded, then it could utilize all that space to embed its data steganographically as opposed to being confined to a maximum of 32 bits provided by the 4 8-bit RGBA channels present in this image.

Before continuing, let me first introduce the idea of least significant bit (LSB) steganography for the uninitiated: steganography is the act of embedding a plaintext inside of a covertext, and LSB steganography is one such method for embedding data inside of images as well as other formats that are insensitive to minute bit-level changes in a potentially large series of (typically) consecutive bytes.

A digital image may contain up to 4 color planes: red, green, blue, and alpha (transparency), each able to express their own intensities using 8 bits; 0 is low-intensity and 255 is high-intensity, with 0 and 255 respectively being the minimum and maximum values that can be represented with 8 bits. Combinations of these color planes can express up to 16,777,216 colors plus transparency. Here’s what (R,G,B,A) = (255, 0, 255, 255) looks like, for instance:

The working principle behind LSB steganography is that the human eye cannot detect extremely small changes in color. Here are two colors that differ by only one bit in each color plane, excluding the alpha plane:

R G B A

255 67 128 255 Left

254 66 129 255 Right

I couldn’t tell the difference – could you? This flaw of our cognitive limitations allows a unique exploit targeting our biology itself: data can be steganographically embedded in the least significant bits of color planes in consecutive pixels of an image while simultaneously having a virtually perfectly invisible effect on the image itself. Even if a person were to have some sort of superhuman cognition and be able to accurately tell the difference between two minutely different colors, they would only be able to determine the differences if they had both the original and altered image. What we need is a computer – which sees color not as a perception and effect of biology, but as ones and zeroes – to extract the data from the least significant bits.

The following colors encode the ASCII letter “A” in their least significant bits, excluding the alpha channel:

It looks like nothing but a white strip, but closer inspection of the individual colors reveals the message:

R G B R G B LSB-R LSB-G LSB-B

254 255 254 11111110 11111111 11111110 0 1 0

254 254 254 => 11111110 11111110 11111110 => 0 0 0

254 255 255 11111110 11111111 11111111 0 1 1

= 01000001 + 1 excess bit

= 65 'A'

A neat consequence of LSB steganography is that extracting the LSB of any byte can be conveniently expressed as passing the byte through an AND gate with the operand 1 (0000 0001). This allows us to easily express it in a programming language such as Python:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from PIL import Image

def main():

pixels = (

(254, 255, 254),

(254, 254, 254),

(254, 255, 255),

)

LSBs = ""

# Extract the LSBs.

for pixel in pixels:

for plane in pixel:

LSBs += "%s" % (plane & 0x01)

# Print the LSBs.

print(LSBs)

# Decode to ASCII.

print("".join(chr(int(LSBs[i:i+8], 2)) for i in range(0, len(LSBs), 8)))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

010000011

A

Now that we understand LSB steganography, let’s get back to the challenge and run the flag PNG through our script:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from PIL import Image

def main():

img = Image.open("./flag.png")

pix = list(img.getdata())

lsb = ""

# Extract the LSBs from 1337 onwards, due to the hint in the description.

for pix in pix[1337:]:

for plane in pix:

lsb += "%s" % (plane & 0x01)

# Decode to ASCII.

print("".join(chr(int(lsb[i:i+8], 2)) for i in range(0, len(lsb), 8)))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Okay… not what we were looking for. Could it be that we have to exclude the alpha channel? Let’s try that:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from PIL import Image

def main():

img = Image.open("./flag.png").convert("RGB")

pix = list(img.getdata())

lsb = ""

# Extract the LSBs from 1337 onwards, due to the hint in the description.

for pix in pix[1337:]:

for plane in pix:

lsb += "%s" % (plane & 0x01)

# Decode to ASCII.

print("".join(chr(int(lsb[i:i+8], 2)) for i in range(0, len(lsb), 8)))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

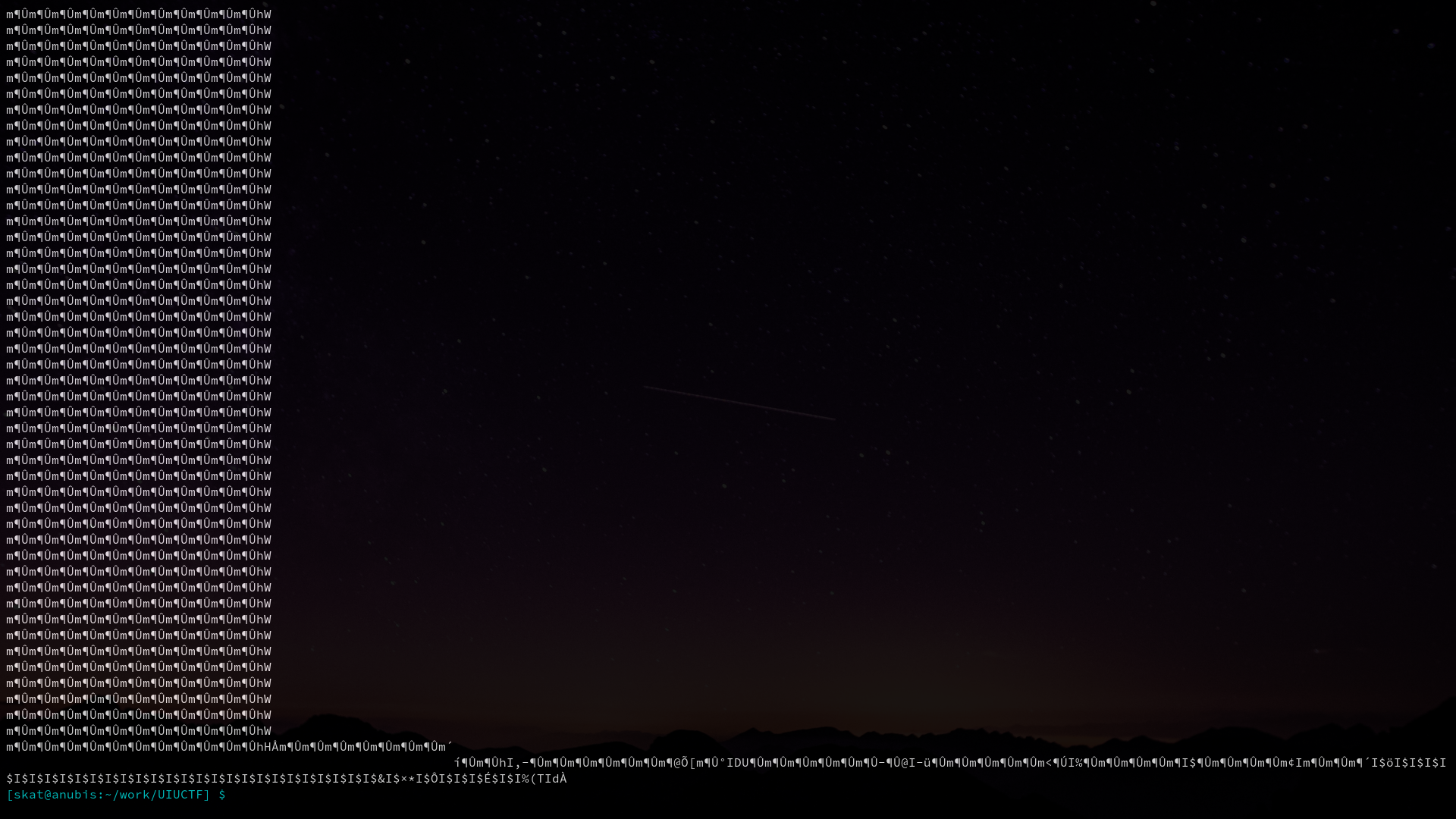

That… wasn’t it either. What’s going on here? Could our hunch about this being an LSB steganography challenge have been wrong? Perhaps the description was a red herring? Why-oh-why didn’t this work? I was stuck for a few hours until an announcement was posted in the event Discord:

Judging by my reaction in my team’s Discord, you could probably get the sense that I wasn’t too happy:

Downloading the new emoji, I could see that it was indeed changed. Here’s the new flag:

Checksum (SHA-1):

c6763e87ce7dfed32408a0f6eaa3e5db9b5a89c8 flag.png

This was where I took a probably unintended approach to the problem. Without much more context from the challenge author, I had assumed that the original flag was simply broken. Assuming that the new flag was fixed, I figured that I could compare the original flag with the new flag to find the differences and get a better idea of how the flag was embedded.

Although I had initially deleted the original flag from my system and downloaded the new flag the moment I saw that announcement out of frustration, Discord does not retroactively update emojis. To get a copy of the original flag, I simply just had to go to an occurrence of the flag emoji from before it was updated. With the original flag and the updated flag, I performed a subtractive operation to find the differences between the original flag and the updated flag:

Seeing that these differences occur in the same column, I realize that this must be a columnar LSB steganography challenge. These differences begin at pixel index 2051 and span for 88 vertically adjacent pixels. Thus, the image being 120 pixels in width, we can add 88 multiples of 120 to our initial starting point of 2051 and extract their least significant bits to hopefully retrieve the flag. We can adapt our Python script to perform this columnar LSB extraction:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from PIL import Image

def main():

img = Image.open("./flag.png").convert("RGB")

pix = list(img.getdata())

lsb = ""

# Extract the LSBs vertically starting from 2051 for 88 pixels.

for i in range(2051, 2051 + 120*88, 120):

for plane in pix[i]:

lsb += "%s" % (plane & 0x01)

# Decode to ASCII.

print("".join(chr(int(lsb[i:i+8], 2)) for i in range(0, len(lsb), 8)))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

uiuctf{d!sc0rd_fl4g_h0w_b0ut_d4t}

Diffing two images to determine how the message was steganographically embedded may not have been what the author had in mind, but it’s a real-life tactic against steganography. By diffing an older variant of the flag with the updated flag, we were able to determine that it was column-based LSB steganography starting at pixel index 2051 and spanning for 88 vertically adjacent pixels. We adapted our script and retrieved the plaintext message successfully.

That was how I solved this challenge. The “Pixels[1337]” hint probably meant index 1337 column-wise, but pixels aren’t indexed column-wise. Even with the hint in the updated flag, “LSBs(Pixels[1337:]),” I would assume that most people who tried this challenge relied too heavily on the validity of the description in conjunction their own (correct) knowledge that pixels in an image are indexed left-to-right, row-by-row. This was, in actuality, an extremely easy challenge, but the given information was misleading in meaning and did not, at any time, be a part of my solution to this challenge; I took an unintended approach instead.