dicecraft

Categories: re

2022-02-07

by not_really

DICECRAFT!

Usage: ./dicecraft <save.dat>

Controls:

- WASD: move

- left shift / right mouse: interact

- F: toggle fly

- space: fly up / jump

- N: fly down

- 0123456789rtyuio: place block

- P: save game (if launched with a save file)

Note: different binary versions are provided for compatability. They are all exactly the same source code, you can pick whichever one you want to reverse :)

Files: chal.dat dicecraft_linux_x64 dicecraft_macos_x64 dicecraft_win10.exe

Exploring

DICECRAFT!

Usage: ./dicecraft <save.dat>

Controls:

- WASD: move

- left shift / right mouse: interact

- F: toggle fly

- space: fly up / jump

- N: fly down

- 0123456789rtyuio: place block

- P: save game (if launched with a save file)

Note: different binary versions are provided for compatability. They are all exactly the same source code, you can pick whichever one you want to reverse :)

Files: chal.dat dicecraft_linux_x64 dicecraft_macos_x64 dicecraft_win10.exe

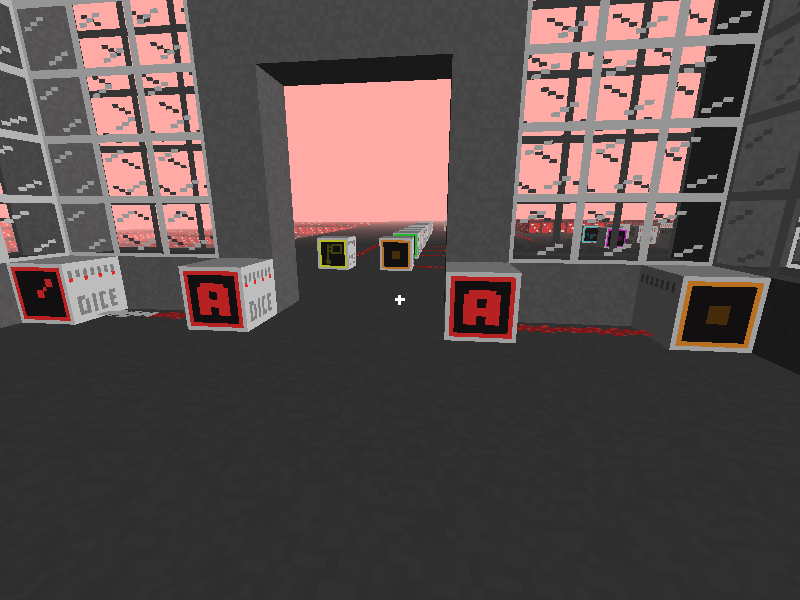

This challenge is a Minecraft clone with computers. Loading up the chal.dat world, we are greeted with a few computers that show off the mechanics.

The red spinning computer on the left seems to send a signal out on a timer. The orange square computer on the right sends a signal when right clicked. The redstone in this game is a bit different from redstone in Minecraft in that it doesn’t power the entire wire at once, it instead shoots off a signal to its destination.

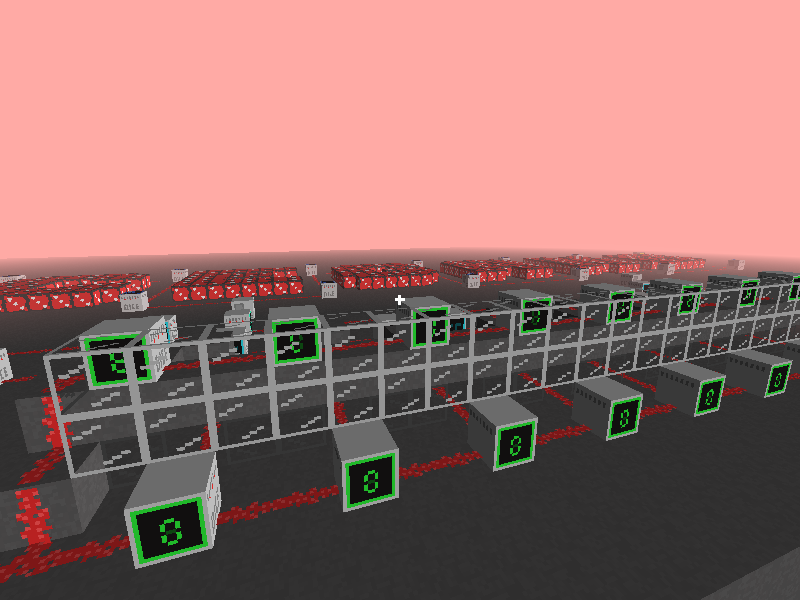

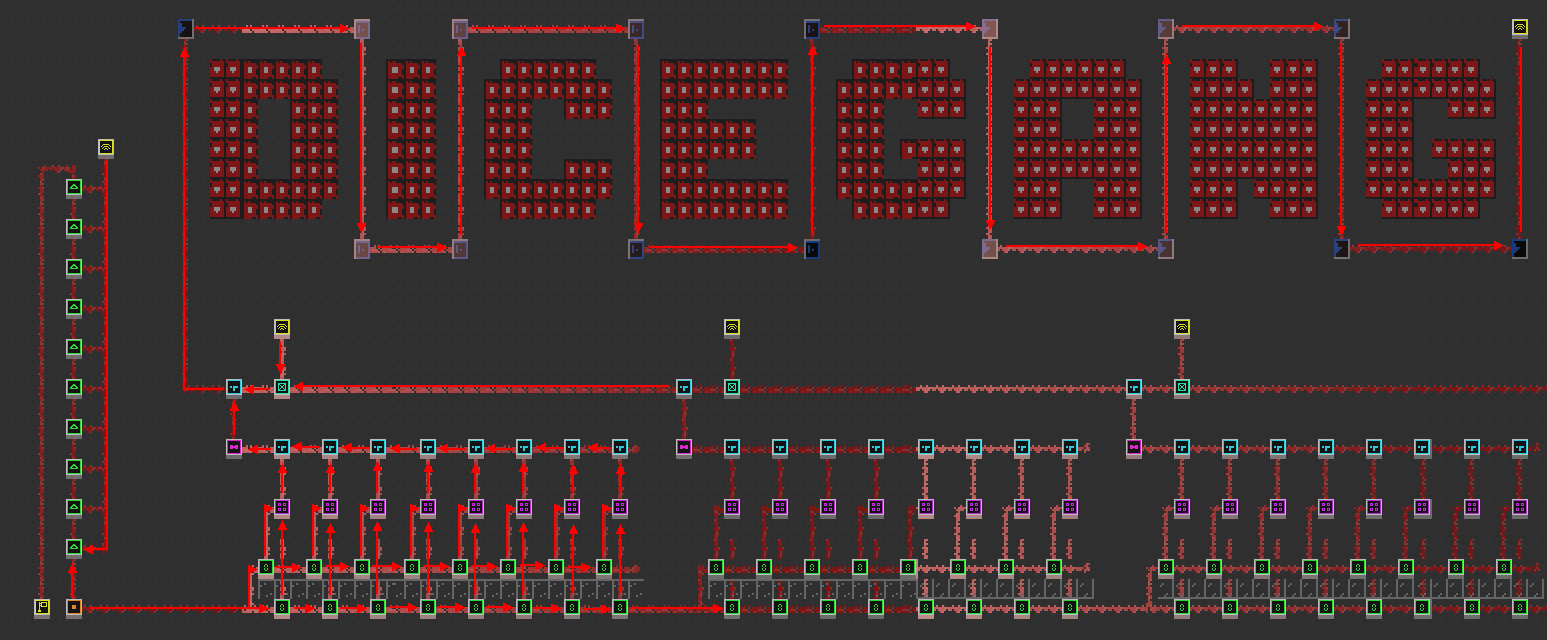

Outside the starting room is a big contraption with a lot of “computers”.

We can right click on these computers on the bottom to cycle them through hex characters (0-f) so this is probably where we put the flag.

There’s also an orange button on the very left which seems to “activate” the circuit.

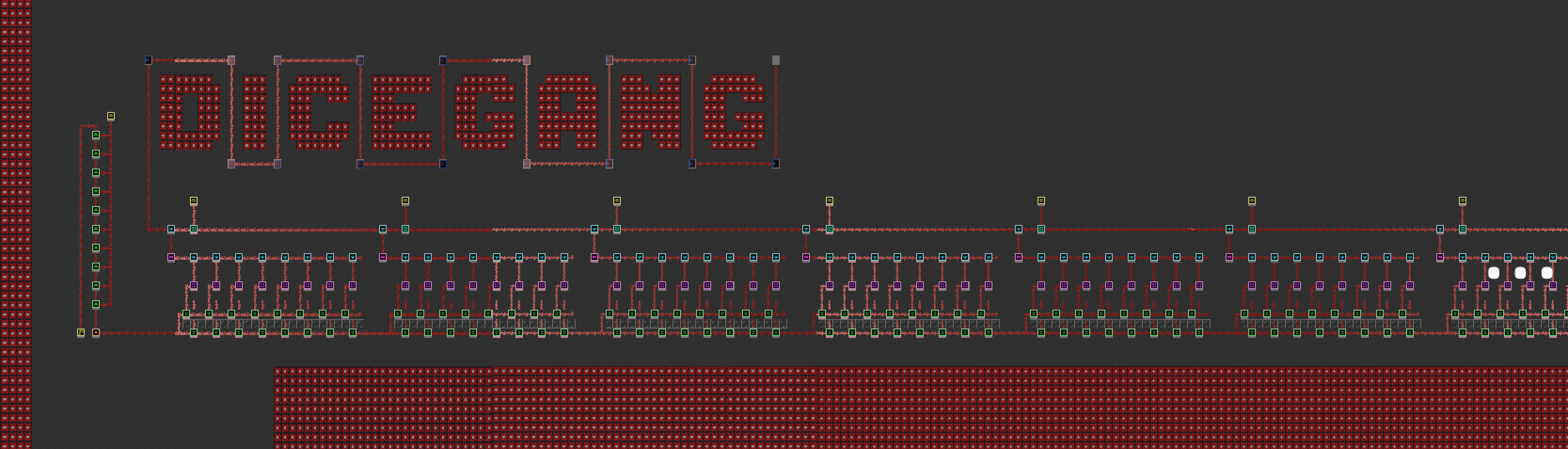

Here’s what it looks like from a birds-eye view.

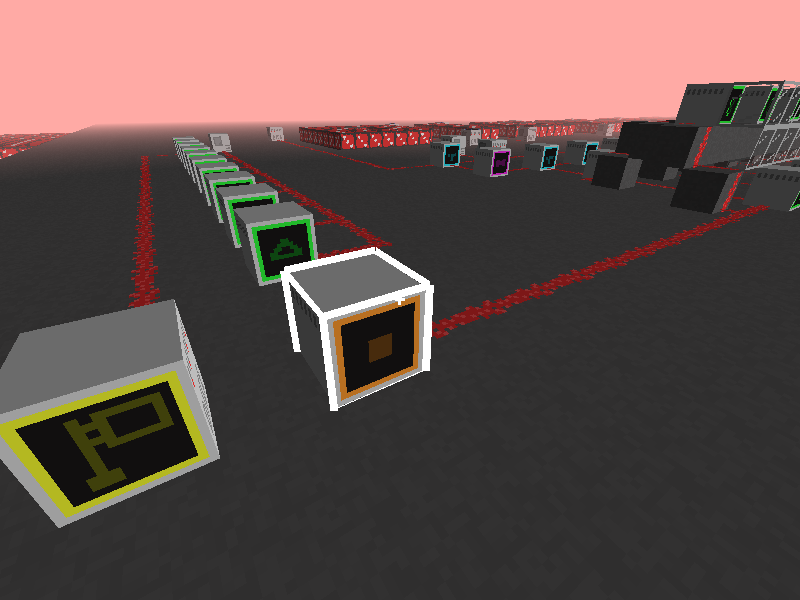

We know the orange block is a button, the red block is a timer, the green block cycles through hex characters, and the letter block just cycles through “DICEGANG”. 1-4 are pretty obvious.

I tried playing around with the blocks a little but it wasn’t exactly clear how many of the blocks worked. So before I get into how each block works, I want to talk about how to get the names of these.

Block names

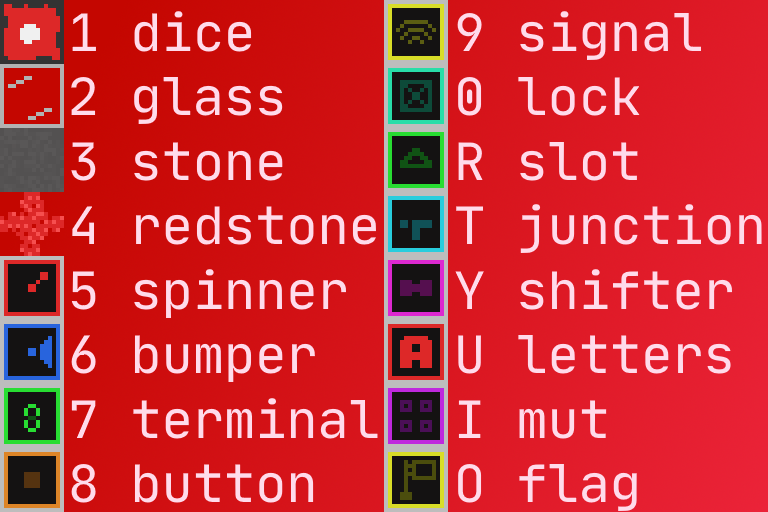

Here’s the key mapping of each block:

If you open the game binary in Ghidra (IDA does not show this), you’ll find the vtable listings. Here are the computers it lists:

BumperComputer

ButtonComputer

FlagComputer

JunctionComputer

LettersComputer

LockComputer

MutComputer

ShifterComputer

SignalComputer

SlotComputer

SpinnerComputer

TerminalComputer

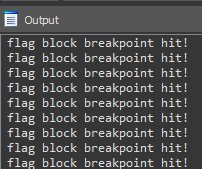

The vtable has 6 functions, so we can set breakpoints and log which computer that breakpoint belongs to. The first function in the vtable is shared between blocks, so we’ll try the second function which seems to be unique to every block.

In doing this, we also find out that the second function appears to be an update as it’s called pretty often.

Just like I did with the update function, I set a breakpoint on the other functions for a few blocks to see if I could figure out what they all did.

Understanding the computer functions

fun0(): called when right clicked.

fun1(): called on a "tick" (i.e. all the time).

fun2(side, value): called whenever a signal goes into it.

fun3(): called on some blocks to return a value. the spinner returns its spin direction for example.

fun4(val): empty on all except terminal. changing the input value changes its initial starting number.

fun5(dir, value): called when a signal comes out of the computer.

Computers also do different things depending on the direction the inputs. We can set a breakpoint on fun2 (signal in) and make signals from each side of the block to figure out what numbers mean what sides.

front: 0

back: 1

left: 2

right: 3

With that out of the way we can look at the code for each computer.

Terminal Computer

Terminal Computer

Right click on this block to cycle it from 0-f hex characters. Any signals from the left are passed onto the right and another signal goes out of the back. These are at the very bottom of the map.

This block is a bit interesting and made me realize that redstone could carry data values in this version. Breaking on fun5 shows that the value on the terminal is indeed the value that comes out of the computer.

Signal Computer

Signal Computer

Sends a signal to other signal blocks. Signals go in the front and out the back on all other signal blocks. You don’t really need to look at the code to figure this out. This block is used at the top right and left of the “DiceGang” dice blocks, as well as behind every group of terminals.

Junction Computer

Junction Computer

Takes inputs into the front and right and passes them along to the left.

Slot Computer

Slot Computer

Takes an input in the front and holds it. Whenever a signal comes in from the left or right, the signal that came in through the front is released out the back.

Lock Computer

Lock Computer

Very similar to the slot computer except it uses an internal counter. Whenever signals come in from the side, the counter increases and whenever signals come in through the front this counter decreases. Whenever the counter is 0, signals will be held like the slot computer until it receives a signal from the side.

Mut Computer

Mut Computer

This computer is a little weird. It takes two values, one from the front and the other from the left. It then adds them together and uses the result as an index into another table.

this->field_0xe = 1;

uVar1 = thunk_FUN_00421d20(this->field4_0x4, this->field5_0x8);

this->field_0x10 = uVar1;

this->field6_0xc = false;

this->field_0xd = 0;

Ghidra does not correctly decompile FUN_421d20, so here’s some psuedo code:

int FUN_421d20(int a, int b) {

int table[16] = {7, 9, 5, 6, 14, 10, 12, 8, 1, 2, 13, 15, 4, 11, 0, 3};

return table[((a & 0xf) + (b & 0xf)) % 16];

}

Shifter Computer

Shifter Computer

Takes eight inputs from the right and sends one signal out the back. At this point, I only thought signals were supposed to be 0x0-0xf because of the terminal computer. However, a quick look at the code shows that the eight inputs are put into one large number.

this->field_0x4 = 0;

this->field_0xc = this->field_0xc << 4 + this->field_0x8;

this->field_0x10++;

if (this->field_0x10 == 8) {

this->field_0x10 = 0;

this->field_0x11 = 1;

}

Bumper Computer

Bumper Computer

This block is strange in that at first glance, any inputs seem to redirect in a random direction (or sometimes no direction at all). These are only used around the dice blocks spelling out Dice Gang. I originally thought these were for decoration only, but the code shows a different story.

undefined8 __thiscall AutoClass::BumperComputerCtor(undefined4 *param_1) {

undefined8 uVar1;

thunk_FUN_00418c90((undefined4 *)this);

*(undefined ***)this = BumperComputer::vftable;

this->field_0x4 = 0xd1c40677;

this->field_0xc = false;

this->field_0x10 = 0;

uVar1 = __RTC_CheckEsp(this,this);

return uVar1;

}

void __thiscall AutoClass::BumperComputerInputIn(undefined4 param_1, uint param_2) {

if (((this->field_0x14 == 0) && (this->field_0xc == false)) && (this->field_0x15 == false)) {

this->field_0xc = true;

this->field_0x10 = param_2;

}

return;

}

void __thiscall AutoClass::BumperComputerUpdateTick() {

byte bVar1;

uint uVar2;

if (this->field_0xc == false) {

bVar1 = this->field_0x14;

if ((AutoClass1 *)(uint)bVar1 == (AutoClass1 *)NULL) {

if (this->field_0x15 != false) {

this->field_0x15 = false;

}

} else {

this->field_0x14 = 0;

this->field_0x15 = true;

}

} else {

this->field_0xc = false;

if (this->field_0x10 != 0) {

uVar2 = this->field_0x10;

this->field_0x10 = this->field_0x10 >> 2;

this->field_0x4 = this->field_0x4 << 0xd ^ this->field_0x4;

this->field_0x4 = this->field_0x4 >> 0x11 ^ this->field_0x4;

this->field_0x4 = this->field_0x4 << 5 ^ this->field_0x4;

if (this->field_0x10 != 0) {

this->field_0x4 = this->field_0x4 * this->field_0x10 ^ this->field_0x10;

}

this->field4_0x4 = (uint)((byte)uVar2 & 3) + this->field_0x4;

pAVar3 = (AutoClass1 *)(this->field_0x4 / 4);

switch(this->field_0x4 % 4) {

case 0:

this->field_0x8 = 0;

break;

case 1:

this->field_0x8 = 1;

break;

case 2:

this->field_0x8 = 2;

break;

case 3:

this->field_0x8 = 3;

}

this->field_0x14 = 1;

}

}

}

When created, it has an initial value in field_0x4 (0xd1c40677) and when powered this value changes and is shuffled around with the input signal’s value (field_0x10). Then, that value is used to determine the output direction (field_0x8). In other words, it’s essentially a seeded random that is controlled by the value of the signal going in each time. We’ll get to why this is important later.

Unimportant blocks:

Letters Computer

Letters Computer

Cycles through letters when powered. Just used as an example in the starting room but nowhere else.

Flag Computer

Flag Computer

Once powered, stays on forever.

Understanding the circuit

So now with a bit of understanding on the blocks, it should help in figuring out how the circuit works.

Here’s the map again with arrows:

It’s a little bit easier to understand what’s going on now. When you click orange button, it powers these first 16 terminal computers. The mut computer adds the values of pairs of terminal computers, one which was already preset with the world, and the other which is input from what is probably the flag. After that, it’s fed into a shifter computer which combines all eight signals into one, and then it goes to the bumper computers.

After it goes through the bumper computers to the end, it hits the signal computer which signals two things. One, it signals the lock computer to unlock, bringing the next signal (from the next shifter computer) to go through the bumper comptuer maze to test the next eight hex characters. The second is to unlock the slot computer on the very left of the map. The slot computers act like a counter, as more parts of the flag are verified, the slot computers get closer and closer to activating the flag computer.

We can test the machine by putting a value we know is correct into the first computers: “dice” (of “dice{XXX}”) which is 64696365 in hex. If we put in anything else for the first eight computers, the signal stops at the bumper computers somewhere along the path. But if they’re set to 64696365, it follows the path all the way to the end and hits the signal computer to signal the next signal.

So the goal is clear, figure out what value allows the bumper computers to carry the signal all the way through. That’s only the output from the mut computer, so we also need to figure out what value needs to go into the mut computer to get the value we want to come out.

As usual, it’s z3 time, and using it was surprisingly simple. All I had to do was create a class to “simulate” what happens to the bumper given an input. Once z3 found the result, I could run through it again to get the “seeds” (the one that starts as 0xd1c40677) and continue on with the next group of characters.

from z3 import *

# initial bumper seed

initSeed = 0xD1C40677

# the directions each bumper needs to go (right, down, right, up, right...)

dirsToMatch = [0,2,0,3,0,2,0,3,0,2,0,3,0,2,0,3]

# every bumper starts with an initial value of 0xD1C40677

seedTemplate = [initSeed] * 16

# simulates bumper computers

class Simulator():

def __init__(self, powerLevel):

self.powerLevel = powerLevel

self.seeds = [0] * 16

# port of BumperComputerUpdateTick code

def simulate(self, index, useSeedsArray):

originalPowerLevel = self.powerLevel

self.powerLevel >>= 2

seed = seedTemplate[index]

seed = ((seed << 13) & 0xffffffff) ^ seed

seed = ((seed >> 17) & 0xffffffff) ^ seed

seed = ((seed << 5) & 0xffffffff) ^ seed

if index != 15: # to make z3 happy

seed = ((seed * self.powerLevel) & 0xffffffff) ^ self.powerLevel

seed += originalPowerLevel & 3

dirResult = seed % 4

dirToMatch = dirsToMatch[index]

if useSeedsArray:

self.seeds[index] = seed

return (dirResult, dirToMatch)

def runSimulation(index):

global seedTemplate

# run simulation for z3

solution = BitVec("sol", 32)

s = Solver()

sim = Simulator(solution)

for i in range(16):

j = sim.simulate(i, False)

s.add(j[0] == j[1])

s.check()

model = s.model()

realSolution = int(model[solution].as_long())

print(realSolution)

# update seeds for next eight hex characters

simReal = Simulator(realSolution)

for i in range(16):

simReal.simulate(i, True)

seedTemplate = simReal.seeds

def main():

for i in range(10):

runSimulation(i)

That gives us the output from the shifter computer, so now we need to reverse that into individual mut computers and figure out what values are needed to make that work.

# these are the values on the top terminal computers

stringEncryptionTable = [

0xC7F55F80,

0xEC0172A7,

0x42C649D1,

0x61F1EFE3,

0xE093FF3D,

0xF433EDE6,

0x141E5834,

0x0241026E,

0xF4F89624,

0x09C64458

]

# this is the scramble table used in the mut computer after adding

stringScrambleTable = [

7, 9, 5, 6, 14, 10, 12, 8, 1, 2, 13, 15, 4, 11, 0, 3

]

# reverses mut computer output by brute force because why not

def decryptString(result, index):

stringEncryptionBlock = stringEncryptionTable[index]

strPieces = 0

for charIdx in range(8):

resPiece = (result >> (28 - (charIdx * 4))) & 0xf

encPiece = (stringEncryptionBlock >> (28 - (charIdx * 4))) & 0xf

for scramIdx in range(16):

if stringScrambleTable[(encPiece + scramIdx) & 0xf] == resPiece:

strPieces <<= 4

strPieces |= scramIdx

break

return bytes.fromhex(hex(strPieces)[2:]).decode("latin-1")

Then all that’s left is to run it!

> python dicecraft_z3_writeup.py

dice

{M1n

3hr4

ft_b

ut_w

1th_

c0mp

ut3Â

s_!!

!!!}

Maybe I messed up a character or two in the stringEncryptionTable but it should say

dice{M1n3cr4ft_but_w1th_c0mput3rs_!!!!!}