UIUCTF 2024 - Time Travel

Categories: re

2024-07-06

by not_really

I used multithreading to check your flag so much slower that it almost feels like time travel.

By: 32121

I used multithreading to check your flag so much slower that it almost feels like time travel.

By: 32121

Takes a flag argument, takes about 20 seconds to check, then prints Bad.

$ ./timetravel a

..................................................Bad

$

The challenge appears to be a VM executing a program from a hardcoded list of bytes. Each instruction is a single byte with no operands. The program heavily relies on threads as the description says.

I will admit, it took me longer than I would like to admit to realize the challenge was brainfuck related. The pointers that can be moved left and right, the 30000 sized buffer, and other things should have tipped me off early on had I actually used brainfuck before.

Once I realized what it was, I searched brainfuck multithreaded and found “brainfork”, which didn’t match what I was looking at in the code at all. It took a while before I realized that I should have been searching for brainfuck time travel instead (I stupidly assumed the “time travel” was part of the program, not of the engine.) That brought up 5d Brainfuck With Multiverse Time Travel.

5dbfwmtt

The explanation on the wiki, as well as a lack of documentation made this a little annoying to understand, as well as being a little different.

Before we get into 5dbfwmtt, let’s talk about how brainfuck works. There are two pointers: the instruction pointer and the tape pointer. The instruction pointer starts at the first instruction and works forward until two things happen. Either the instruction pointer reaches the end of the program (exit) or a [ or a ] is hit. The [ jumps to the next ] on the right if the value pointed by the tape pointer is 0, and ] jumps to the next [ on the left if the value pointed by the tape pointer is not 0. These two are used for both conditionals and looping. The last two instructions are , and ., the input and output instructions. The input instruction reads a single character from input and the output writes the value pointed by the tape pointer to output. Pretty simple.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

> (01) |

Move tape pointer right |

< (02) |

Move tape pointer left |

+ (03) |

Increment value at tape pointer |

- (04) |

Decrement value at tape pointer |

, (05) |

Read next byte value from program argument (flag input) |

. (06) |

Output byte value at tape pointer to terminal |

[ (07) |

Jump to next right ] if value at tape pointer is zero |

] (08) |

Jump to next left [ if value at tape pointer is not zero |

The simplest new thing with 5bdfwmtt is the ~ instruction, which reverses a single operation on the tape. Note that this doesn’t affect any tape or instruction pointers, only the operations that occurred on the tape. So any +, -, or , operation will be undone. A common operation is [~] which means “rewind until value at tape pointer is 0.” You can increment a certain cell value to take a “snapshot” of the state of the tape, then move the tape pointer to it later and run [~] to restore the tape before that value was incremented.

The other part is the multiverse part which is where things get crazy. The new instructions are (, ), v, ^, / (called @ in the original), |, \, and !. The wiki provides this graphic for how the timeline system works, which we’ll go into more detail below.

main timeline split

-------------------+---------------------------------------------->

| split 2nd timeline dies

2nd timeline +-------+-----------X /------------------------>

| / 3rd timeline replaces 2nd

3rd timeline +-----------/

The ( instruction creates a new timeline (seemingly interchangeable with “universe”) “below” the current one. This copies everything from the current timeline including the pointers and tape. The parent moves its instruction pointer right after the next ) on the right and the child moves its pointer right after the ( and continues execution until it reaches the ).

The v and ^ instructions push tape pointers to the universe above or below. Wait, what? Pointers with an “s”? Something new to 5dbfwmtt is that universes can have multiple tape pointers. Normally, you start with only one pointer. However, you can gain a pointer by having a parallel universe give you another pointer. When you have more than one pointer, all pointers will have their operations executed at once. For example, if you have three tape pointers at addresses 0, 1, and 2, and you run a + instruction, the values of the cells at 0, 1, and 2 will all increment. Additionally, all pointers move forward and backward at the same time. You can delete pointers by pushing them into the “void” (up as the main universe or down as the lowest universe). v and ^ are really the only methods of sending data between universes.

The /, |, and \ instructions wait until a neighbor universe has no tape pointers. / means wait on the lower universe to have no pointers, | means wait while this universe has no pointers, and \ means wait on the upper universe to have no pointers. 5dbfwmtt normally only supports one of these, the @ instruction. I’ve renamed the @ to / to make them a little more clearer. Note: the \ instruction is never used in the program.

The last two instructions are ! and NOP. The ! instruction stops tape recording for the ~ instruction. And NOP was an instruction that was supposed to be removed, but we’ll see in a bit why this instruction is useful.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

~ (09) |

Rewind a single tape operation |

( (0a) |

Create a new parallel universe with the upper (parent) universe jumping after the next right ) and the new lower (child) universe after the ( , executing until the next ) |

) (0b) |

Does nothing to the main universe and kills all non-main universes. |

v (0c) |

Move all tape pointers to the (next) lower universe |

^ (0d) |

Move all tape pointers to the (previous) upper universe |

/ (0e) |

Wait on the lower universe to have no pointers |

| (0f) |

Wait until this universe has pointers |

\ (10) |

Wait on the upper universe to have no pointers |

! (11) |

Disable history for ~ |

NOP (12) |

Do nothing |

disassembly

Here is my simple disassembly script:

indent = 0

for v in b:

if v == 0x08 or v == 0x0b:

indent -= 2

print(" "*indent, end="")

match v:

case 0x01:

print("> /* bufptr++ */")

case 0x02:

print("< /* bufptr-- */")

case 0x03:

print("+ /* buf[bufptr]++ (recorded) */")

case 0x04:

print("- /* buf[bufptr]-- (recorded) */")

case 0x05:

print(", /* buf[bufptr] = read() (recorded) */")

case 0x06:

print(". /* write(buf[bufptr]) */")

case 0x07:

print("/* while (buf[bufptr] != 0) */ [")

case 0x08:

print("] /* (while buf[bufptr] != 0) */")

case 0x09:

print("~ /* rewind tape by 1 */")

case 0x0a:

print("/* fork block */ (")

case 0x0b:

print(") /* (end fork block) */")

case 0x0c:

print("V /* move down */")

case 0x0d:

print("^ /* move up */")

case 0x0e:

print("/ /* sleep while lower (next) universe has pointers */")

case 0x0f:

print("| /* sleep while we have no pointers */")

case 0x10:

print("\\ /* sleep while upper (previous) universe has pointers */")

case 0x11:

print("! /* disable history (disable ~) */")

case 0x12:

print("NOP /* nop */")

if v == 0x07 or v == 0x0a:

indent += 2

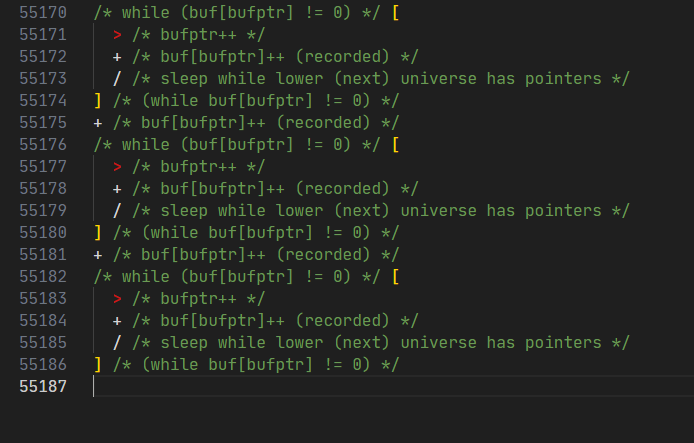

Unfortunately, that makes a 55k line file.

looking at the flag checking code

I always like to start at the end and work backwards. Thankfully, there are very few places where the code prints anything (runs .). At the very top of the file, there are four . prints that seem to print out the Bad text (and presumably the Good text). The code looks like this:

++[--<++]-->[+[-->++]-->+<<++[--<++]-->]++[-->++]-->>+++++>++++++++++<[->[->+<<<->>]>[-<+>]<<]+<[[-]>-<]>

(

(

[++++++[->++++++++++++++<]>+++.[~]]

)

++++++[->++++++++++++++<]>+++.[~]

-[-]+++++++++[->++++++++++<]>+.

)

+++++++++++[->+++++<]>+.

After stepping through it with a brainfuck debugger like this one up until the universe creation code, it becomes obvious what is going on. The code checks if a certain cell is 50 (5*10). If it is, it sets the next cell to 1. Otherwise, it sets it to 0. There are some other things in the code we’ll talk about later like the FE marker.

++[-->++]-- // look for next FE marker

>>

+++++>++++++++++< // write 5, 10 to second and third cells after FE (for 5*10)

// subtract 5*10 from first cell after FE

[

->[->+<<<->>]>[-<+>]<<

]

+<[[-]>-<]> // if cell is 0 (50-50=0), set to 1. otherwise, set to 0.

(

(

[++++++[->++++++++++++++<]>+++.[~]] // good = "o", 6*14+10+3

)

++++++[->++++++++++++++<]>+++.[~] // bad = "a", good = "o", (6+correct)*14+10+3

-[-]+++++++++[->++++++++++<]>+. // bad = "d", good = "d", 9+9*10+1

)

+++++++++++[->+++++<]>+. // bad = "B", good = "G", (11+correct)*5+10+1

So the win condition is somehow setting this cell (following this specific FE marker) to 50. I wrote a GDB script to print out the value of this cell depending on input. The only NOP instruction happens right before all of this goes down, so it’s a perfect place to set a breakpoint and check the tape.

import struct

import gdb

# #####

offAddress = 0

def set_break_event(callback, addr, inst=None):

class GdbBreakpoint(gdb.Breakpoint):

def __init__(self, callback, addr, inst):

global offAddress

super(GdbBreakpoint, self).__init__("*" + hex(addr + offAddress), type=gdb.BP_BREAKPOINT, internal=False)

self.callback = callback

self.inst = inst

def stop(self):

pos = read_reg("rip")

res = None

if inst == None:

res = self.callback(pos)

else:

res = self.callback(inst, pos)

return res == True

GdbBreakpoint(callback, addr, inst)

def get_entry_point():

ENTRY_POINT_STR = "\tEntry point: "

fileInfo = gdb.execute("info file", to_string=True)

infoLines = fileInfo.splitlines()

for line in infoLines:

if line.startswith(ENTRY_POINT_STR):

entryPoint = int(line[len(ENTRY_POINT_STR):],0)

return entryPoint

return None

def read_reg(reg):

gdbValue = gdb.selected_frame().read_register(reg)

return int(gdbValue.cast(gdb.lookup_type("long")))

# ###

gdb.execute("set print addr off")

gdb.execute("set print thread-events off")

gdb.execute("set pagination off")

gdb.execute("set confirm off")

gdb.execute("set disassembly-flavor intel")

gdb.execute("set debuginfod enabled off")

def read_mem(addr, len):

i = gdb.inferiors()[0]

return i.read_memory(addr, len)

def read_mem_u64(addr):

i = gdb.inferiors()[0]

b = i.read_memory(addr, 8)

return struct.unpack('<Q', b)[0]

def dump_tl_mem(addr):

timeline_addr = read_mem_u64(read_reg("rsp") + 0x10)

first_chunk_addr = timeline_addr + 0x18 + 1

b = read_mem(first_chunk_addr, 0x100)

print(b)

return False

gdb.execute(f"file timetravel", False)

fileAddress = get_entry_point()

gdb.execute("starti")

offAddress = get_entry_point() - fileAddress

set_break_event(dump_tl_mem, 0x2669) # NOP instruction code

test = input("flag: ").ljust(50, "A")

gdb.execute(f"run \"{test}\"")

exit(0)

Assuming the program actually starts (it very often does not), you can enter a value and see what the cell’s value is. Typing nothing gives you 0. Typing uiuctf{ gives you 7. And changing the ljust length parameter from 50 to 41 gives you an additional 9. So this value represents the amount of characters we have right, and the length of the flag is 41.

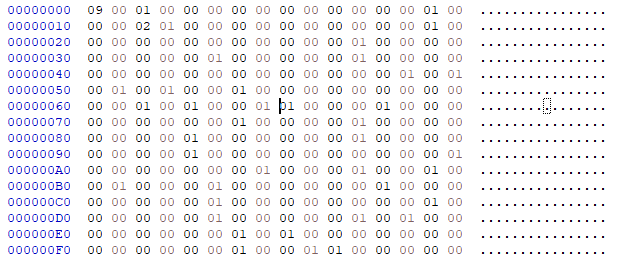

Looking at the dump for a single a character, the tape looks like this:

If you change the a to anything else like a b, the 01 byte at the cursor in the screenshot moves to a different cell in a sporadic way. If you have the right character, in this case u, the 01 moves into the first cell, and 09 is incremented to 0a. So the goal is to move all of these 01s to the first cell somehow. Note that the value of one character and its 01 position does not affect other characters and their 01 positions.

I looked for quite a while for any pattern in the movement. If that was possible, I could write a script to move each character a few times to figure out its movement, then calculate what character would need to make that move to the first cell. However, each increment of the byte value of a character seemed to move it somewhere unpredictable. I decided it was probably easier to just brute force this than to understand it.

brute forcing it

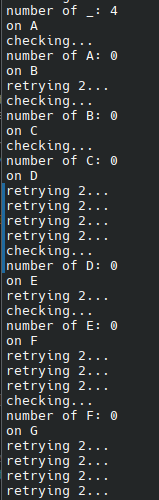

Brute forcing this challenge would have been not all that bad, had a certain weird debugger issue been present. Both IDA and GDB often struggled to run the program. While I never encountered this when running the program normally, the debuggers I used would get stuck somewhere at the beginning at the program and launch only a few threads. So how do you detect a “getting stuck” moment and how do you get it “unstuck”? Since GDB blocks until a breakpoint is hit or ctrl+c is pressed by the user, having just a single script to handle the stuckness wouldn’t work. So I wrote a Python script to run the second Python GDB script multiple times and to restart when it failed.

from pwn import *

def generate_test_str(c):

# necessary since certain letters in this spot

# cause the program to lock up

return c*19 + "A" + c*21

test_chars = "_ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789"

test_char_idx = 0

test_char = test_chars[0]

while True:

test_str = generate_test_str(test_char)

p = process(["gdb", "-q", "-ex", f"py guess='{test_str}'", "-x", "ttt.py"])

res = p.recvuntil(b'Using host libthread_db library', timeout=3)

if res == b"":

p.close()

print("retrying 1...")

continue

res = p.recvuntil(b"...", timeout=1)

if res == b"":

p.close()

print("retrying 2...")

continue

print("checking...")

res = p.recvuntil(b"success[", timeout=30)

if res == b"":

p.close()

print("retrying 3...")

continue

corr_str = p.recvuntil(b"]")[:-2]

corr = int(corr_str.decode()) - 9 # remove 9 correct empty characters

print(f"number of {test_char}: {corr}")

test_char_idx += 1

test_char = test_chars[test_char_idx]

print(f"on {test_char}")

And the update to the original script:

# ...

def dump_tl_mem(addr):

timeline_addr = read_mem_u64(read_reg("rsp") + 0x10)

first_chunk_addr = timeline_addr + 0x18 + 1

b = read_mem(first_chunk_addr, 0x100)

print("success value", b[0][0])

return False

# ...

set_break_event(dump_tl_mem, 0x2669)

if "guess" not in vars():

print("guess argument not passed!")

gdb.execute("quit")

exit(0)

guess = guess.ljust(41, "A")

gdb.execute(f"run \"{guess}\"")

exit(0)

And then if we run the script (python3 -u ttt_parent.py SILENT | tee ttchars.txt) we’ll get output like this:

After about 25 minutes, we get these non-zero characters (including uiuctf but not {}):

number of _: 4

number of H: 1

number of N: 1

number of P: 1

number of R: 1

number of b: 1

number of c: 2

number of d: 1

number of f: 2

number of g: 1

number of i: 1

number of l: 3

number of m: 1

number of p: 1

number of t: 5

number of u: 3

number of w: 2

number of 0: 1

number of 1: 2

number of 3: 1

number of 4: 2

number of 5: 1

or in one line, ____HNPRbccdffgilllmptttttuuuww0113445{}. This is missing one because of one of the characters causing the program to freeze, but we can guess that one when it’s the last character left.

Finally we can brute force each character individually using the above character set:

from pwn import *

def generate_test_str(c, idx):

return "A"*idx + c + "A"*(40 - idx)

def check_char(test_char, idx):

while True:

test_str = generate_test_str(test_char, idx)

print(test_str)

p = process(["gdb", "-q", "-ex", f"py guess='{test_str}'", "-x", "timetraveltest.py"])

res = p.recvuntil(b'Using host libthread_db library', timeout=3)

if res == b"":

p.close()

continue

res = p.recvuntil(b"...", timeout=1)

if res == b"":

p.close()

continue

res = p.recvuntil(b"success[", timeout=30)

if res == b"":

p.close()

continue

corr_str = p.recvuntil(b"]")[:-2]

corr = int(corr_str.decode()) - 9 # remove 9 correct empty characters

return corr > 0

def check_all_chars():

test_chars = list("____ttttlllww1144bcdfgmpu035HNPR")

test_char_idx = len("uiuctf{")

flag = ""

while test_char_idx < 41:

found_char = False

uniq_test_chars = list(dict.fromkeys(test_chars))

for test_char in uniq_test_chars:

res = check_char(test_char, test_char_idx)

if res:

found_char = True

flag += test_char

test_chars.remove(test_char)

break

if not found_char:

flag += "?"

print(flag)

test_char_idx += 1

if test_char_idx == 19:

flag += "?"

test_char_idx += 1

check_all_chars()

This returns _p4R4ll3l_c0?Put1Ng_w1tH_5dbfwmtt? after about 2 hours, and guessing the missing character as M, we get uiuctf{_p4R4ll3l_c0MPut1Ng_w1tH_5dbfwmtt}.

Solution:

$ ./timetravel uiuctf{_p4R4ll3l_c0MPut1Ng_w1tH_5dbfwmtt}

..................................................Godo

$

Oh cute, even the correct message is having a threading issue. :3

what is it actually doing?

Before we get more into it, I want to add some clarification about universes a little bit better than the wiki does. The list of universes is one-dimensional. When a parallel universe/timeline is created, it is always inserted between the current universe and the would be next universe. For example, Let’s say these timelines exist:

main timeline split

-------------------+---------------------------------------------->

|

2nd timeline +---------------------------------------------->

It’s very obvious how these timelines are relative to each other. The main timeline has no upper timeline but a lower timeline (2nd timeline). Likewise, the 2nd timeline has no lower timeline but an upper timeline (main timeline). If you add a 3rd timeline below the 2nd timeline, this is all fine, but what happens if we add a timeline in-between the main and 2nd timeline? It will look something like this:

main timeline split split

-------------------+---------------+------------------------------>

| |

| 3rd timeline +------------------------------>

|

2nd timeline +---------------------------------------------->

Does the 2nd timeline know about the 3rd timeline and vice versa? The answer is yes. If the 2nd timeline were to push pointers up, it would push them into the 3rd timeline, despite branching off of the main timeline after the main timeline before the 3rd timeline was created. And the same for the opposite, the 3rd timeline can push pointers down into the 2nd timeline. It’s easier to think of the timelines like a list:

main timeline

3rd timeline

2nd timeline

Creating a new parallel timeline/universe is the same as inserting into this list. Reaching the end (the ) character) is the same as removing an item from this list.

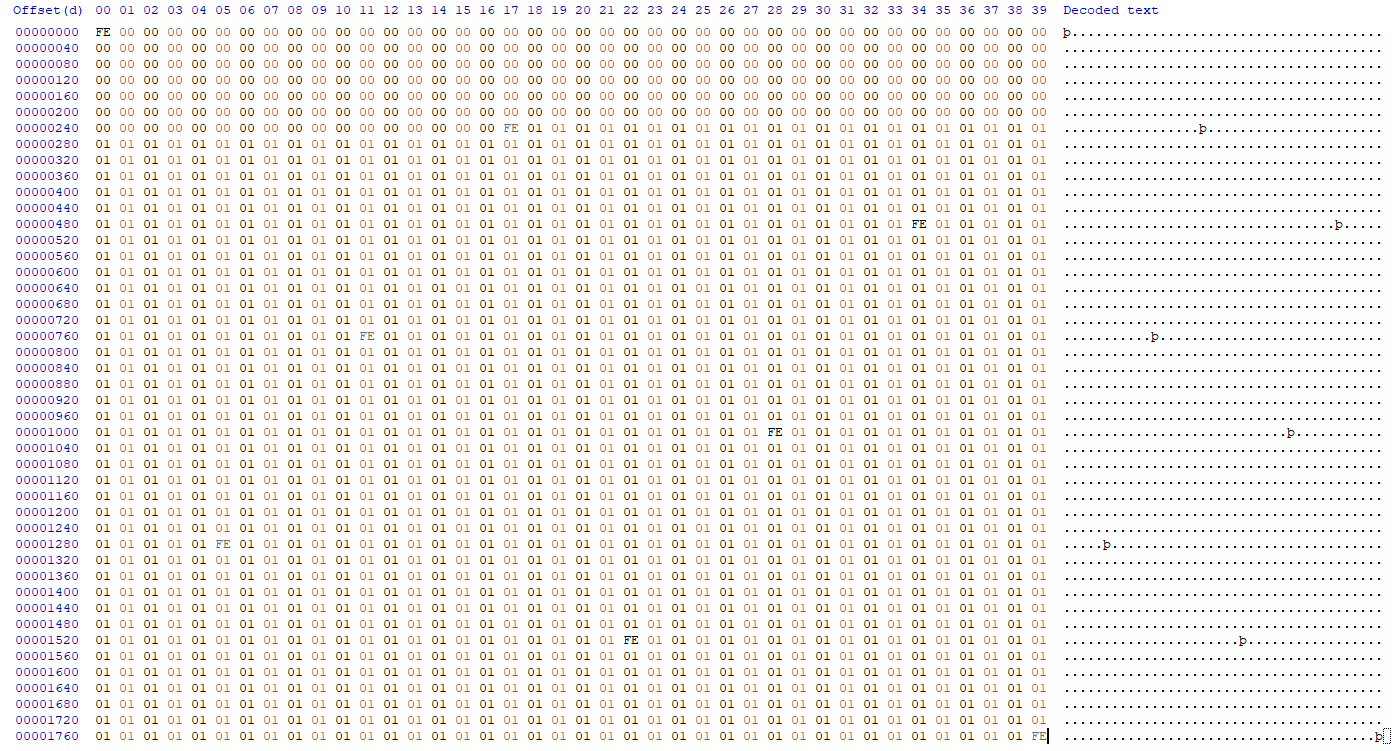

There’s a lot of brainfuck to look at, so here’s a map of the program to make things easier to explain (with 1-indexed addresses):

1: Place eight FE markers with 0x100 cells with value 01 in between

118: Go to second FE block

204: New universe: final check and print Good or Bad (the part we saw above)

611: Go to third FE block

623: New universe: ??? (we'll refer to it as the "apple universe")

note: more universes are created inside of this one

and all other ??? universes

8567: Go to fourth FE block

8579: New universe: ??? (banana universe)

16758: Go to fifth FE block

16770: New universe: ??? (carrot universe)

26241: Go to sixth FE block

26253: New universe: ??? (donut universe)

37008: Go to seventh FE block

37020: New universe: ??? (egg universe)

51895: Go to eighth FE block

51968: New universe: read next input char (or FF if no more input exists)

.....: This 49 more times

55116: Wait on program to finish

55187: End of program

To wrap our heads around the multiple timelines, let’s look at a common pattern in the “??? universes”:

( // child 1

( // child 2

( // child 3

!|/V|/V|/V|/V|/V ...

do things

)

!|/V|/V|/V|/V|/V ...

do things

)

!|/V|/V|/V|/V|/V ...

do things

)

This creates a timeline that looks like this:

main timeline split

-------------------+---------------------------------------------->

| split

child 1 +-------+-------------------------------------->

| split

child 2 +-------+------------------------------>

|

child 3 +------------------------------>

But wait a second, isn’t child 3 the lowest most timeline? Is it really using V to push its tape pointers down into the void? If this was the only code in the program, then that would be true, but the lowest level timeline is the earliest (still running) timeline in the program, which in our program is the final check and print Good or Bad universe. So if the code looked like this:

( // final check

do things, but don't exit before child 1,

child 2, and child 3 have exited

)

// some other stuff here

( // child 1

( // child 2

( // child 3

!

|/V|/V|/V|/V|/V ...

do things

)

!

|/V|/V|/V|/V|/V ...

do things

)

!

|/V|/V|/V|/V|/V ...

do things

)

The timeline would look like this:

main timeline split split

-------------------+--------------+------------------------------->

| | split

| child 1 +-------+----------------------->

| | split

| child 2 +-------+--------------->

| |

| child 3 +--------------->

final check +---------------------------------------------->

So the inner-most child (child 3) will push its tape pointers into final check, not into the void.

A high-level view of all of the timelines is this:

main timeline split split split split split

----------------+---...---+--------+--------+------------+------------+---------->

| | | | | |

| | | inp 1 +---X inp 2 +---X inp 3 +---X .....>

| | |

| | | split

| | egg 1 +---+----------------------------------------->

| | | split

| | egg 2 +---+------------------------------------->

| | |

| | egg 3 +------------------------------------->

| | split

| donut 1 +---+-------------------------------------------------->

| | split

| donut 2 +---+---------------------------------------------->

| |

| donut 3 +---------------------------------------------->

|

| ... repeat until apple timeline

|

final check +---------------------------------------------------------------->

Input starts at each input timeline and is passed down into the outer-most egg timeline all the way to the inner-most donut timeline. From there, it’s passed into the inner-most carrot timeline, and so on. Once it reaches the inner-most apple timeline, it’s passed into the final check. If you’re wondering about the order these timelines exit in, setting a print breakpoint on the ) instruction shows that they exit in reverse order (starting with egg, ending with apple, and final check being… well, final.)

timeline hit ) at: 52027 // first input char

timeline hit ) at: 52089 // second input char

// ... 48 times for the the rest of the input

timeline hit ) at: 51894 // start of egg

timeline hit ) at: 42058

timeline hit ) at: 40478

timeline hit ) at: 39537

timeline hit ) at: 38497

timeline hit ) at: 37007 // start of donut

timeline hit ) at: 31331

timeline hit ) at: 30374

timeline hit ) at: 28915

timeline hit ) at: 27328

timeline hit ) at: 26240 // start of carrot

timeline hit ) at: 21665

timeline hit ) at: 20310

timeline hit ) at: 19257

timeline hit ) at: 17870

timeline hit ) at: 16757 // start of banana

timeline hit ) at: 12890

timeline hit ) at: 11590

timeline hit ) at: 10576

timeline hit ) at: 9674

timeline hit ) at: 8566 // start of apple

timeline hit ) at: 6272

timeline hit ) at: 5110

timeline hit ) at: 3956

timeline hit ) at: 2320 // final check

memory visualization

Before anything happens, a bunch of FE markers are placed on the tape. These markers are used to move the tape pointer to certain parts of the program. This is because brainfuck doesn’t have an instruction to tell where the pointer is at, but it can easily check if the current tape is pointing to a 0. So the code often adds two to the current cell, checks if zero, subtracts two again to put the value back, and moves left or right if it wasn’t zero.

Notice how each region between the FE markers are 0x100 in size? That will be important later.

flag input universes

The simplest of universes are the 50 flag input reading ones. They all mostly work the same. They all start by printing a . character using some multiplication. Then, the tape pointer is moved forward n+k times (where n is the value of the input character and k is some hardcoded constant, usually only 3-4). The tape pointer is pushed down into the outer-most egg universe, and it exits to run the next flag universe.

??? universes

The ??? universes seem complicated and very large, but looking looking at pieces of the code separated by /V| makes the code a little easier to understand. The gist of each one of these is simple: either immediately pass along the modified flag pointer you receive from the above universe, or do some modification to the pointer received. Again, I recommend putting these through a debugger to see what they’re doing. The copy.sh one is good at showing memory, the kvbc one is good at stepping but hard to see memory, and the ashupk fork has an animation but limited memory.

At a high level, it looks like this, where X is some kind of modification.

egg 1 egg 2 egg 3 donut 1

inp 1 ---X-------------------------->

inp 2 ----------X------X------------>

inp 3 -------------------------X---->

inp 4 ---X-------------X------------>

So what’s the modification? The code moves the pointer a certain amount forward/backward depending on if you add or subtract a character value. If you hit an X, the character is added to, otherwise nothing happens. As the author puts it, it’s an arbitrary base system. In order to wrap around, whenever the tape pointer hits one of the FE bytes, the pointer wraps around to the other FE byte (in other words, mod 256).

It converts binary to a different base so for [48, 29, 31, 190, 175, 252, 211, 4] and a number 151, 151 == 0b10010111 => 48 + 190 + 252 + 211 + 4 == 193 (mod 256)

Note that there are 24 ??? universes that input can pass through. Presumably only 8 of those hit one of these operations before ending up at the end.

I didn’t write a script to solve it this way, but it’s probably possible to do somehow! Potentially taking a snippet of the code, running it through a brainfuck interpreter, and seeing what happened?