CalATMity

Categories: re

2020-07-24

by not_really

Uh oh! The circuitry on the Nook stop got a little messed up and it’s not letting you withdraw your bells! How will you pay off your loan now?

nc chal.uiuc.tf 2005

Author: Eric

Files: calatmity

Uh oh! The circuitry on the Nook stop got a little messed up and it’s not letting you withdraw your bells! How will you pay off your loan now?

nc chal.uiuc.tf 2005

Author: Eric

Files: calatmity

I realized there was still a rev problem 30 min before the competition ended and didn’t finish before the end. Well, there was no way I was finishing it under 30 minutes. I still solved it though because I was curious after the competition ended.

First off, this program’s in rust which means Ghidra isn’t gonna be able to do jack.

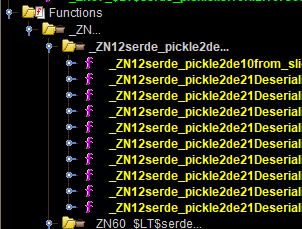

While I was waiting for it to decompile anyway, I was looking at the Decompiling loading bar at the bottom right and saw these pickle functions being decompiled:

Along with “Deserializer”, it made me think it was python’s pickle format, the binary format for storing python objects. Sure enough, a search gave me https://github.com/birkenfeld/serde-pickle. Weird that we have python serialization in a rust project.

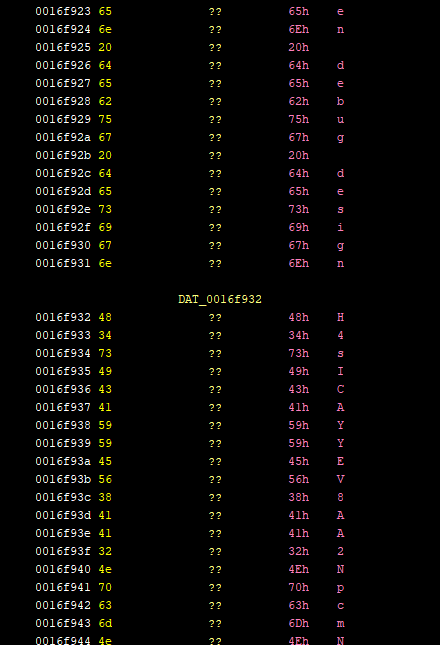

I wanted to see if I could find the function referencing the “Thanks for using the Nook stop!” string so I tried searching for the string. Turns out it’s a non-terminated string, and Ghidra doesn’t know any better. However, as I was looking through the top of the string, I found this base64:

Okay, let’s unencrypt it. (I copied the base64 out with a hex editor)

import base64

s = "H4sICAYYEV8AA2NpcmN1aXQucGtsAO2cedhOxRvHeTchOxGVUiTRvkiLJUUnUUQiRXqT..."

with open("somedecodedb64", "bw") as sdb64:

sdb64.write(base64.b64decode(s))

Let’s see what file we got out of it:

C:\Users\notrly\Documents\csictf\clam>file somedecodedb64

somedecodedb64: gzip compressed data, was "circuit.pkl", last modified: Fri Jul 17 03:16:22 2020, from Unix, original size modulo 2^32 54947

Okay, then we can extract circuit.pkl from the gzip and deserialize it with pickle.

>>> import pickle

>>> f = open("circuit.pkl", "rb")

>>> pickle.load(f)

{'gates': [{'op': ('NOT',)}, {'op': ('AND',)}, {'op': ('AND',)}, ...}

{'netlist': [[1, 131], [2], [3], [4], [5, 8], [92], [7], [8], [9]...}

So this is the “circuitry” the description was talking about. Assuming that each gate has an array in netlist, let’s just print out some info and see what we get.

import pickle

with open("circuit.pkl", "rb") as f:

g = pickle.load(f)

gateCount = len(g["gates"])

for gateIdx in range(gateCount):

gateType = g["gates"][gateIdx]["op"][0]

connectedGates = ""

for netIdx in g["netlist"][gateIdx]:

connectedGates += str(netIdx).zfill(4) + " "

print(f"gate {str(gateIdx).zfill(4)} type {gateType} connected to {connectedGates}")

gives us

...

gate 0130 type XOR connected to 1399

gate 0131 type AND connected to 0132

gate 0132 type NOT connected to 0133

gate 0133 type AND connected to 0134 0755 0967

gate 0134 type XOR connected to 0135

gate 0135 type XOR connected to 0136 1132 1137

gate 0136 type NOT connected to 0137

gate 0137 type AND connected to 0138 0139 1343 1418

gate 0138 type NOT connected to 0149

gate 0139 type AND connected to 0140

gate 0140 type NOT connected to 0151

gate 0141 type AND connected to 0142 0171 0172 0727

gate 0142 type XOR connected to 0145 1382

gate 0143 type AND connected to 0144

gate 0144 type NOT connected to 0147

gate 0145 type AND connected to 0146

gate 0146 type NOT connected to 0147

gate 0147 type AND connected to 0148 1141

...

So in a normal (logic) circuit, we can expect there to be inputs and outputs. and and xor should have two inputs and not should have one input. But some gates like 0141 have more than 2. Most likely those are where those gates output to. We’ll have to come up with the inputs ourselves.

gateCount = len(g["gates"])

for gateIdx in range(gateCount):

gateType = g["gates"][gateIdx]["op"][0]

fromGates = ""

toGates = ""

netIdx = 0

for net in g["netlist"]:

if gateIdx in net:

fromGates += str(netIdx).zfill(4) + " "

netIdx += 1

for netIdx in g["netlist"][gateIdx]:

toGates += str(netIdx).zfill(4) + " "

print(f"gate {str(gateIdx).zfill(4)} type {gateType} connected from {fromGates}connected to {toGates}")

gives us

...

gate 0130 type XOR connected from 0042 0127 connected to 1399

gate 0131 type AND connected from 0000 1527 connected to 0132

gate 0132 type NOT connected from 0131 connected to 0133

gate 0133 type AND connected from 0132 1658 connected to 0134 0755 0967

gate 0134 type XOR connected from 0033 0133 connected to 0135

gate 0135 type XOR connected from 0117 0134 connected to 0136 1132 1137

gate 0136 type NOT connected from 0135 connected to 0137

gate 0137 type AND connected from 0136 1722 connected to 0138 0139 1343 1418

gate 0138 type NOT connected from 0137 connected to 0149

gate 0139 type AND connected from 0137 1805 connected to 0140

gate 0140 type NOT connected from 0139 connected to 0151

gate 0141 type AND connected from 1501 1528 connected to 0142 0171 0172 0727

gate 0142 type XOR connected from 0141 1796 connected to 0145 1382

gate 0143 type AND connected from 1722 1806 connected to 0144

gate 0144 type NOT connected from 0143 connected to 0147

gate 0145 type AND connected from 0142 1723 connected to 0146

gate 0146 type NOT connected from 0145 connected to 0147

gate 0147 type AND connected from 0144 0146 connected to 0148 1141

...

It seems to all be working good. We can see not with only 1 input and and and xor (lol) with two inputs. But wait a second, how does this help us get that 16 digit pin? Well there’s gotta be inputs into the circuit. Let’s see if we have any connections that aren’t from gates.

gateCount = len(g["gates"])

netListCount = len(g["netlist"])

# check for any outputs that don't have gates

print("outputs")

for net in g["netlist"]:

for netIdx in net:

if netIdx >= gateCount:

print(netIdx)

# check for any inputs that don't have gates

print("inputs")

for netIdx in range(netListCount):

if netIdx >= gateCount:

print(netIdx)

gives us

outputs

1885

inputs

1821

1822

1823

...

1882

1883

1884

So 1821-1884 are input lines and 1885 is an output line, probably telling us if our input is correct. So now we have to find the right combination of 0s and 1s of 1821-1884 to give us a 1 from 1885. Time for z3 solver. I had heard of people using it for this type of thing but had never used it myself. A quick search brought me here for some example code.

from z3 import *

ar = [BitVec(f'{i}', bitsOfEachNum) for i in range(numCount)]

s = Solver()

s.add(condition1)

s.add(condition2)

print(s.check()) # should be sat

model = s.model()

print(model)

results = ([int(str(model[ar[i]])) for i in range(len(model))])

Since we only want 1885 to be 1, there’s really only one condition here. And we should try to convert the “circuit” into a parsable condition.

import pickle

def gateName(gateIdx):

return f"gate{str(gateIdx).zfill(4)}"

with open("circuit.pkl", "rb") as f:

g = pickle.load(f)

of = open("circuit.pkl.z3", "w")

gateCount = len(g['gates'])

netCount = len(g['netlist'])

def getGateText(gateIdx):

if gateIdx >= 1821:

return f"ar[{gateIdx-1821}]"

xRefs = []

gateType = g['gates'][gateIdx]['op'][0]

for netIdx in range(netCount):

net = g['netlist'][netIdx]

if gateIdx in net:

xRefs.append(netIdx)

if gateType == "AND":

return f"({getGateText(xRefs[0])} & {getGateText(xRefs[1])})"

elif gateType == "XOR":

return f"({getGateText(xRefs[0])} ^ {getGateText(xRefs[1])})"

elif gateType == "NOT":

return f"({getGateText(xRefs[0])} ^ 1)"

of.write("s.add(" + getGateText(1476) + " == 1)\n")

of.close()

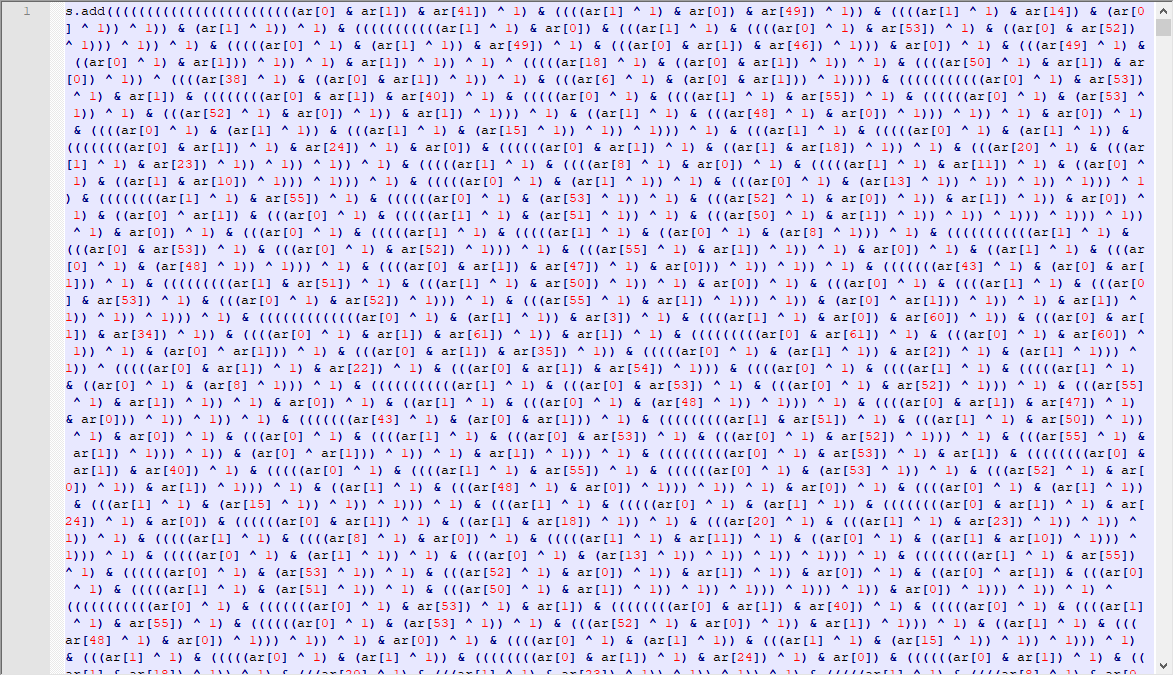

If you treat each gate as a function, I’m essentially inlining all of the functions into one expression.

So if we run that, we get this huge block of code:

Then all we have to do is wrap it in the z3 boilerplate code I pasted earlier.

from z3 import *

ar = [BitVec(f'{i}', 1) for i in range(64)] # 1 bit, 64 inputs

s = Solver()

s.add(...)

print(s.check())

model = s.model()

print(model)

results = ([int(str(model[ar[i]])) for i in range(len(model))])

print(results)

And if we run it?

[29 = 1,

60 = 0,

61 = 1,

...

48 = 1,

47 = 1,

8 = 0]

[1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0]

Yay, we got it! let’s convert these bits to an int.

out = 0

for bit in results:

out = (out << 1) | bit

print(out) # 17465288031635233796

That’s it right? Let’s put it in.

Thanks for using the Nook stop! Please enter your 16-digit PIN:

17465288031635233796

We need 16 digits (for security)

Thanks for using the Nook stop! Please enter your 16-digit PIN:

Welp, looks like our number is too large. Maybe we can flip the bits?

results = results[::-1]

out = 0

for bit in results:

out = (out << 1) | bit

print(out) # 2322729860550919759

Still too many digits. Well, let’s look at how many bits are in in the biggest 16 digit number, 9999999999999999:

>>> len(bin(9999999999999999))-2 #-2 to get rid of 0b

54

Okay, so if the biggest number has 54 bits, the top 10 bits should be 0.

def getGateText(gateIdx):

if gateIdx >= 1831:

return f"ar[{gateIdx-1831}]"

if gateIdx >= 1821:

return f"0"

(Once you run the z3 code generator again, make sure to change ar’s range from range(64) to range(54).)

unsat

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "C:\Python38\lib\site-packages\z3\z3.py", line 6696, in model

return ModelRef(Z3_solver_get_model(self.ctx.ref(), self.solver), self.ctx)

File "C:\Python38\lib\site-packages\z3\z3core.py", line 3759, in Z3_solver_get_model

_elems.Check(a0)

File "C:\Python38\lib\site-packages\z3\z3core.py", line 1385, in Check

raise self.Exception(self.get_error_message(ctx, err))

z3.z3types.Z3Exception: b'there is no current model'

Rip, maybe 63/line 1884 is the most significant bit, not 0/line 1821.

def getGateText(gateIdx):

if gateIdx >= 1874:

return f"0"

if gateIdx >= 1821:

return f"ar[{gateIdx-1821}]"

That gives us

[29 = 0,

37 = 1,

3 = 1,

...

48 = 1,

47 = 1,

8 = 0]

[1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1]

Yay, we got another valid result.

results = results[::-1] # flip because rightmost bit is most significant

out = 0

for bit in results:

out = (out << 1) | bit

print(out) # 7879797576737871

Weird, it’s hex for xyyuvsxq. 🤷

Anyway, let’s put it into the nc.

Thanks for using the Nook stop! Please enter your 16-digit PIN:

7879797576737871

uiuctf{th0nks_4_st0pping_by3}

Imho, the point value of this (350) and cricket32 (500) should have been swapped. I would say this was definitely a much harder problem than cricket was.

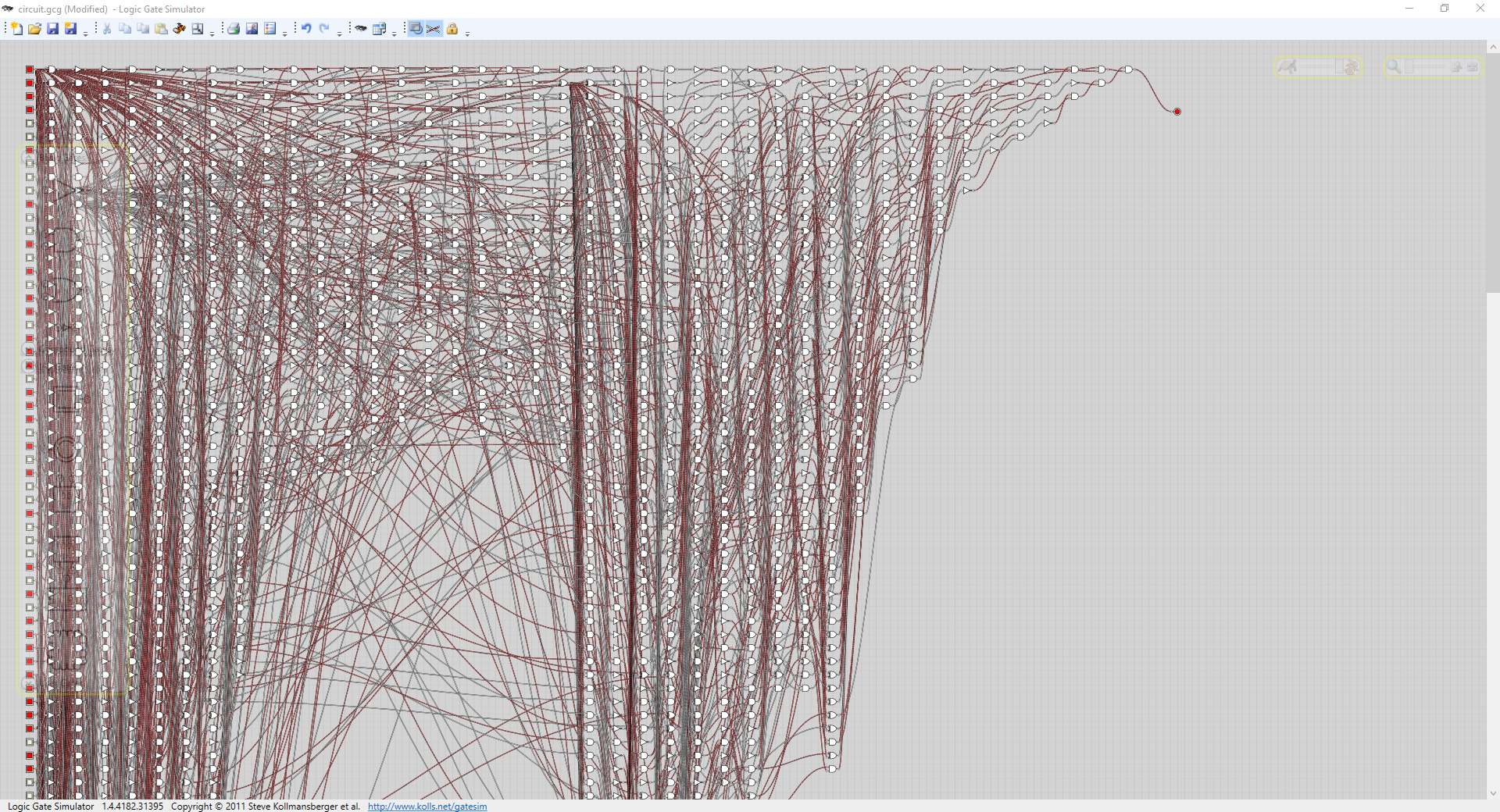

By the way, you might be interested in seeing what this circuit would look like “physically”. Well, I have it for you. The whole circuit generated in a circuit emulator and the result is 1 when we plug in the binary from earlier.

Code is here but the simulator is on wpf so don’t expect to be able to run on linux.

Graph in its full glory (without the binary set) is here.